Who Owns Collaborative Art: Credit in the World of Comics

Carl Potts published the first mini-series featuring the character Rocket Raccoon, nearly ten years after the gun-toting raccoon first appeared in the Marvel Universe in 1976.

“A lot of the other editors thought I was nuts for putting this thing out,” says Potts, who was an executive editor for most of his 13 years at Marvel Comics.

Rocket Raccoon wasn’t really used again until he featured in the Guardians of the Galaxy comics and blockbuster film. It took thirty years, but Potts was finally vindicated.

Potts spoke about his experiences overseeing Marvel publications while he was at The Banff Centre last week as part of the two-day Story Summit.

The audience of visual storytellers, primed perhaps by the recent discussion surrounding Stan Lee’s real role in creating Marvel’s roster of superheroes, came to learn how Pott’s experience with Marvel taught him how to balance group collaboration and fair credit.

Characters like Rocket Raccoon don’t belong to Potts, but to his creators -- a writer-artist duo. Though as an editor, Potts helped direct the course of several much-loved superheroes.

“I have a nostalgic attachment to a lot of them,” Potts says. “I never took credit for editorial contributions to books I helped develop in my capacity as an editor. I just considered it part of the job.”

Comics’ long-lived characters are a collaborative feat: fleshed out, tested, and modernized by a small army of artists, writers, and colourists.

The company often uses what’s called the “Marvel method”, where writers draft a quick plot summary before sending it to the pencil artist. That artist figures out the number of panels needed to tell the story and adds their own pacing, character quirks, and plot twists.

“Quite often, the writer would get back something that would be a bit different than they envisioned when they first wrote that plot,” Potts says.

This back-and forth-process helps keep content fresh for a while. But when a team stagnates, the comic book series can be traded to another creative crew. For this kind of creative exchange to take place, Potts says the office environment needs to foster a sense of equality. He tried to ensure all his team had basic understanding of the value of everyone else’s role.

Handing off your creative baby can save your character from stagnation or put it at risk, he says.

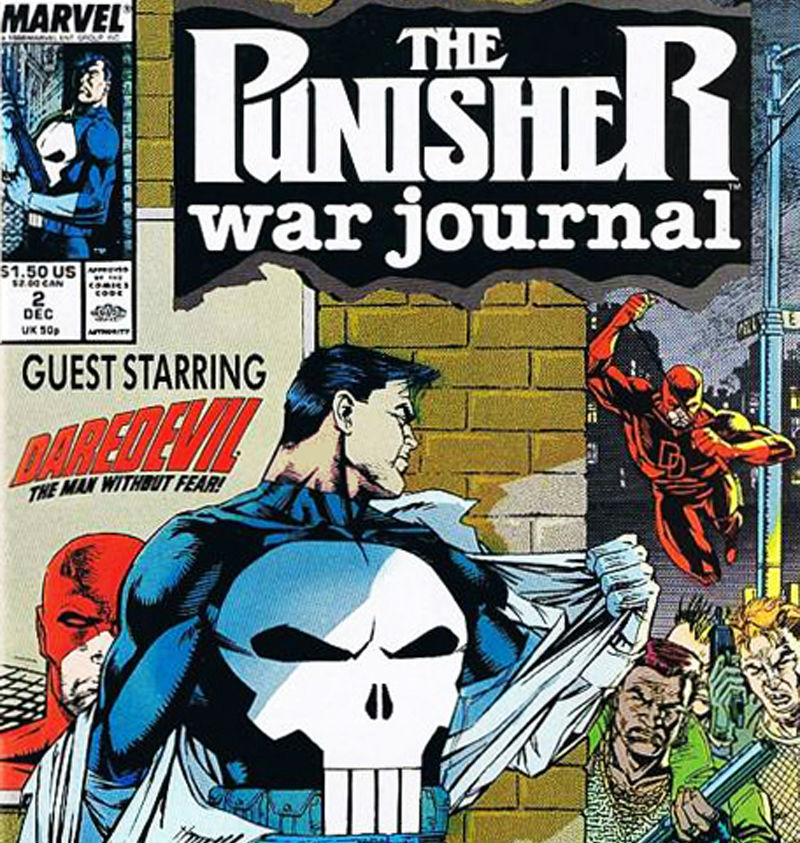

Potts experienced this first hand when he had to give up writing The Punisher War Journal after he was promoted to executive editor.

“You kind of have to do battle with two competing notions. One of which is that evolution can and should be good, but that some people just screw things up.”

The Punisher character existed for many years before Potts developed it into a franchise, but he worked hard to define the traits of the character.

Having the artists and writers on the same page from the beginning helps ensure quality output. Potts cast the Punisher as a two-dimensional anti-hero, so that as his story progressed or when he cameoed in other series he was consistent.

“If there is only one person who knows what the characters are or aren’t, it has got to be the editor. But ideally, everybody on the book is going to have a good feel for the character.”

For larger projects, Potts recommends drafting a “bible” to cement the world’s characters and internal logic. It helps him sort everything out in his head and gives his team a base to work from and add to.

Potts says this approach has helped him successfully take many of his own creations forward, with his sights set on the big screen.

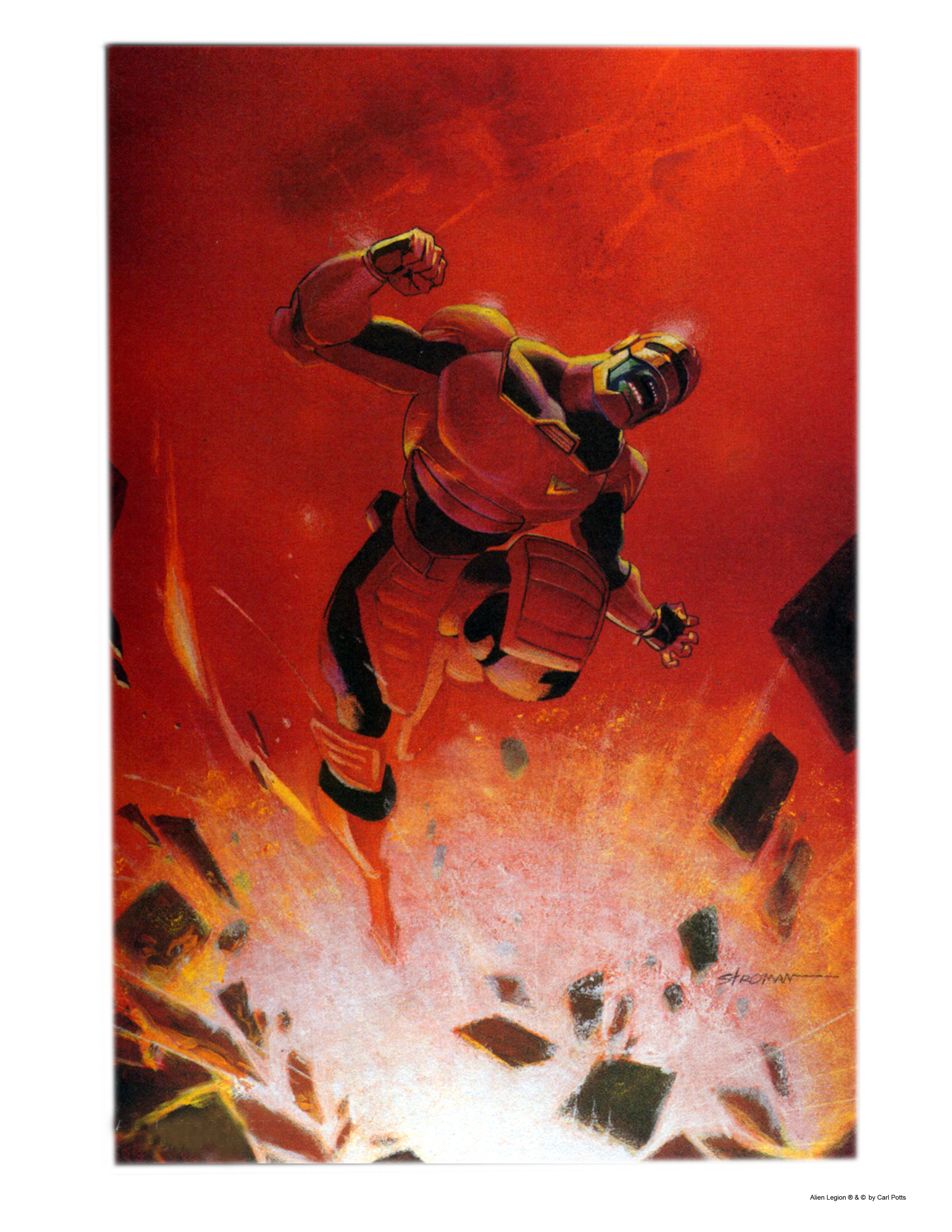

He is currently reaching out to studios with several screenplays. The rights for his comic series, Alien Legion, have been purchased by Bruckheimer Disney.