Some Thoughts on Unthinking

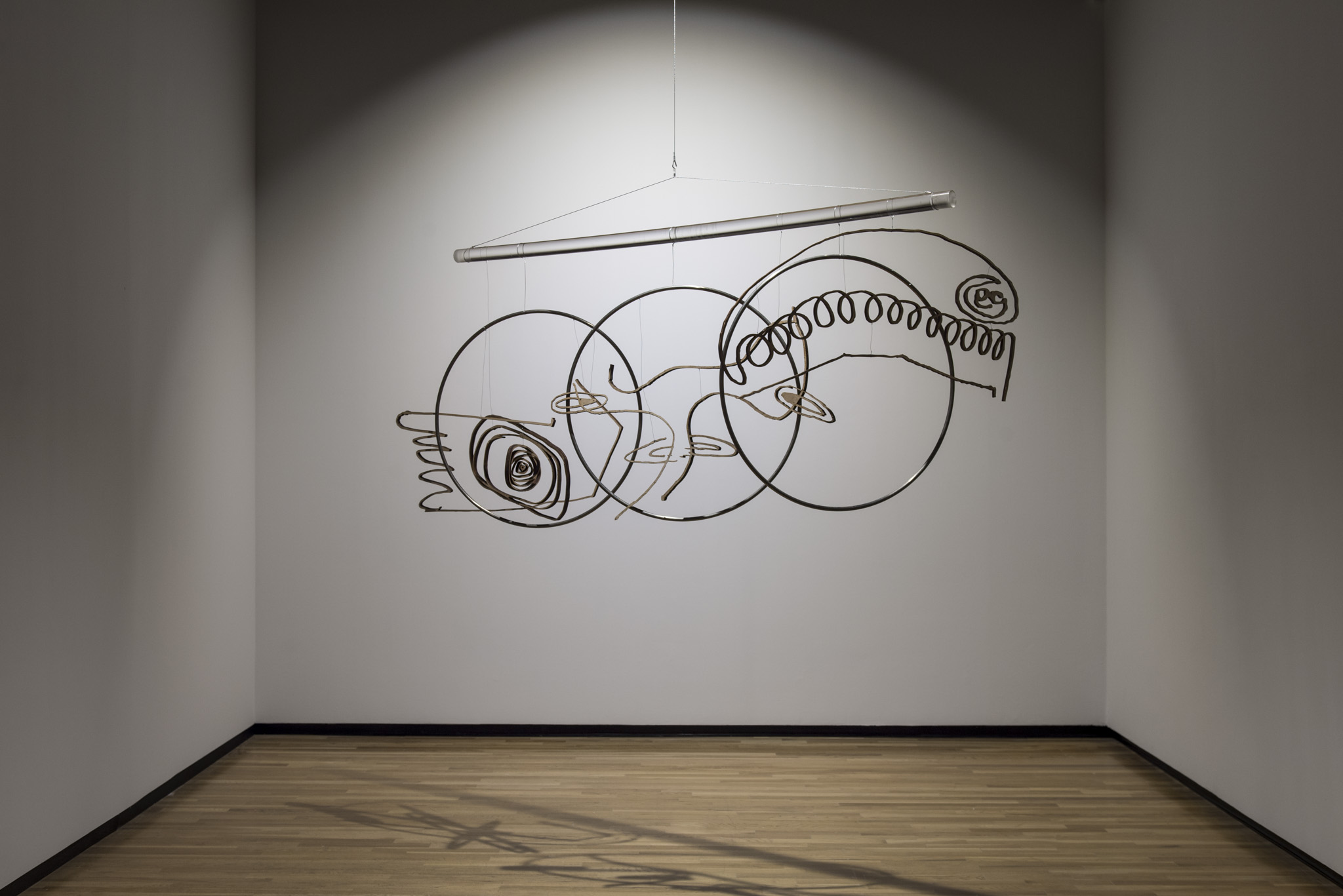

Virginia Lee Montgomery, installation view “Ideation Accelerator Mobile” (2015). Van de Graaff Particle Accelerator artifacts (aluminum, lucite), wire and pine. Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre. Courtesy of the artist and Yale Department of Physics at Wright Lab

Some Thoughts on Unthinking was originally published as a foreward in the exhibition catelogue for "things you can't unthink". More on the exhibition here.

Walter Phillips Gallery has often been a site for mid-career artists to think experimentally in relation to their practices. This exhibition brings together a slightly younger set of voices, all of which are engaged in various dialogues across North America. Many of the artists, all women, included in the exhibition have had touch points in Banff, by way of osmosis, a collegial network or as resident artists. In a similar spirit of collegiality, and activating the individual networks we all have within our own communities, this publication has collected an assembly of critical and interesting voices to think (and unthink) about the intangible.

In the making of exhibitions, there are some things that are intuitive or internalized, yet when others write about your exhibitions, you come to learn more deeply and tangentially about your own curatorial practice. What we know about the objects in this exhibition is rendered multiple through the texts included in this publication, which were shaped in large part by Natasha Chaykowski’s keen editorial eye.

Contributions include Chaykowski’s essay “Thinking makes it so,” which speaks to Erica Prince’s installation, Released From Orbit, Jacqueline Bell’s conversation with Virginia Lee Montgomery, “It’s okay to be many things at once,” Hannah Myall’s poem “Not a line, but a poem” on her relationship to Eunice Luk and her work, and finally Britt Gallpen’s “The Permanence of Things,” on Sara Cwynar’s Contemporary Floral Arrangement series.

As with any exhibition, many minds went into thinking about it, and making it manifest in space, so a huge thank you to the entire Walter Phillips Gallery team that realized the exhibition in all its material practicalities. A special thank you to Sara Cwynar, Eunice Luk, Virginia Lee Montgomery and Erica Prince, the artists included.

Erica Prince, installation view “Released From Orbit” (2012). Mirror, glazed ceramic, wire, found objects, plaster, paper maché, spray painted aluminum foil and lights. Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre. Courtesy the artist

things you can’t unthink speculates on theories of new materialism, its complex and layered relationship to the object-oriented ontology [1] (OOO) movement, and the recent turn towards considering objects as “things” by thinkers in all manner of disciplines. In brief, the tenets of OOO see everything including thoughts as “objects.” No two objects share any relation to one another, and are therefore autonomous beings that sever any “human” thoughts about them—they are meaningful whether or not we perceive them.

Further, all autonomous objects are equal, or “ontologically speaking on the same plane.” [2] OOO’s decentering of the human subject reconciles modern and contemporary art’s established interest in the limits of human perceptual and linguistic understanding when it comes to “objects” and further, the relative independence and internal logic of an artwork. [3]

New materialism is of interest here because, in part, it belies OOO. It is a category of theories generated as a response to the linguistic turn (the focusing of philosophy and the other humanities primarily on the relationship between philosophy and language) that are also linked to feminism. [4] These theories likewise have specific commitments to knowledge-becoming practices, which refer to the way that new materialism thinks about things in the world and what we know about them.

The philosophical proposals of new materialism probe the limits of historical theories attached to Enlightenment ontology (what is in the world) and epistemology (what we know about what is in the world, and how it is classified), wherein things were considered to be separate and unable to affect one another. [5] “Knowing” an object may mean to experience it (a human function) or to name it (a linguistic function), however never in its entirety. It is at this crux that the human re-entered the picture, recognizing that both language and materiality are never complete.

In regard to things you can’t unthink, each artwork maintains its own internal logic (never fully revealed to us), or reveals itself peripherally through what OOO thinker Timothy Morton refers to as the “charisma” of an object, defined as having “a compelling energy.” [6] Art’s relationship to the intangible is interesting in light of these new materialist and OOO tendencies. For Morton, art is almost demonic as, “…it emanates from some unseen (or even unseeable) beyond, in the sense that [we are] not in charge of it and can’t quite perceive it directly, in front of [us], constantly present.”[7]

The demonic, like magic, is unthinkable because its cause and effect are invisible. Here, Morton exemplifies the overlap or in-process part of the debate, because the invisibility of the internal life of an object can only be speculated upon by a human subject. Morton highlights that the art object is different to other “things.” Despite our presence, art remains a charismatic object, one that we allow to be so.

All this to say, things you can’t unthink reflects the inconsistencies and contradictions of these philosophical fields still in flux, or in-thought. The exhibition is an unresolved set of relations, in which artworks are proximate to one another in order to generate new intersections and constellations among them. The works included speak to innovation, craft, history and science, as well as the way in which artistic materials — clay, paint, found objects, metal — are unconventionally employed. The very nature of unthinking is to stop a thought in its tracks — to put something out of mind.

Perhaps this is Morton’s proposition after all; to consider an object anew, to allow an object to perceive us, and depending on how well it coaxes us, for it to let us in.

This article was previously published in the catalogue for the Walter Phillips Gallery exhibition, "things you can’t unthink", and was titled "Some Thoughts on Unthinking" written by Peta Rake.

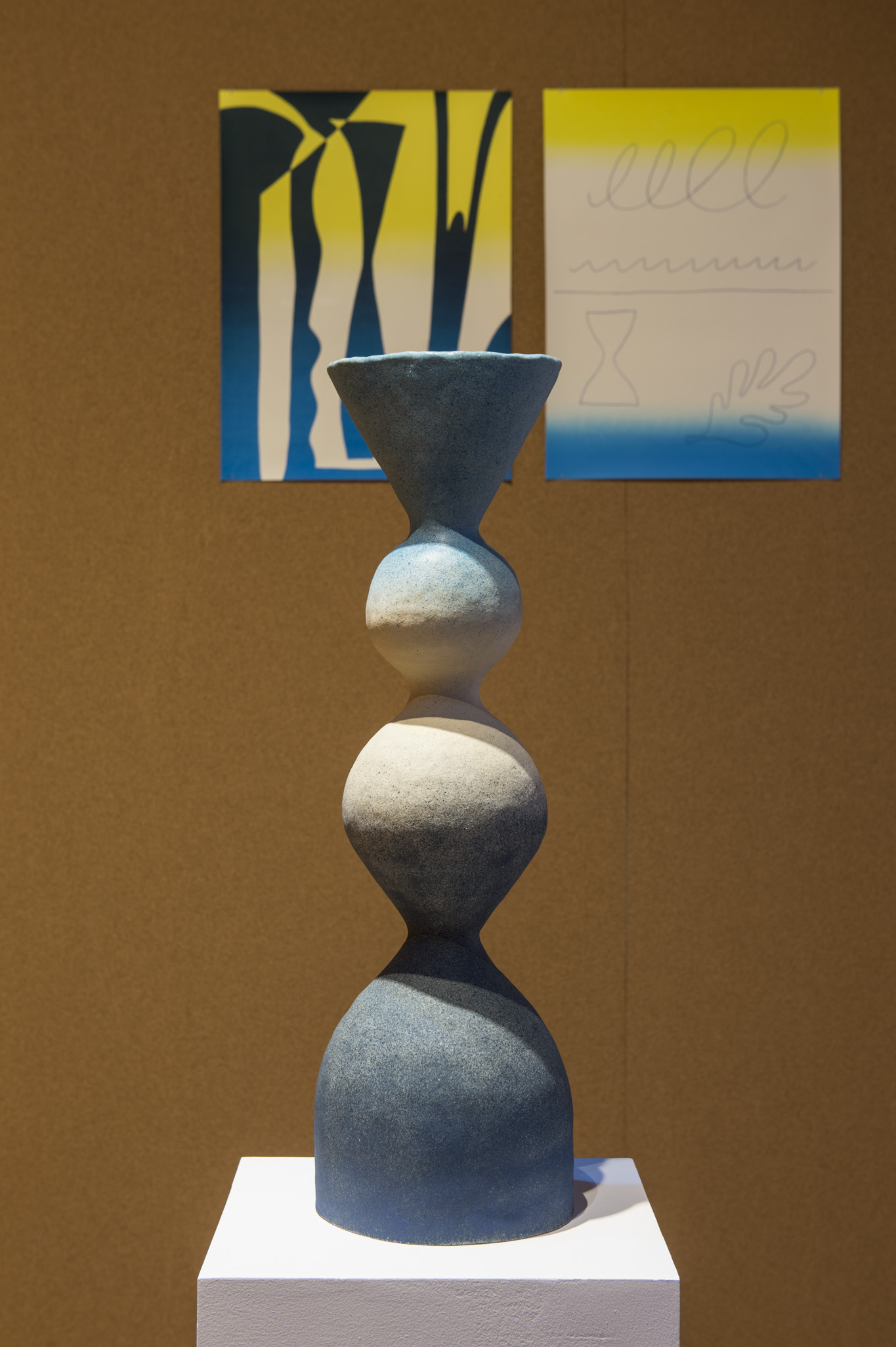

Eunice Luk, installation view “Max height no. 4 (blue, clay to blue)” (2015). Ceramic. Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre. Courtesy the artist

Endnotes

[1] Ontology is the philosophical study of existence. Object-oriented ontology (“OOO” for short) puts things at the center of this study.

[2] Cole, Andrew. “Those Obscure Objects of Desire: The Uses and Abuses of Object-Oriented Ontology and Speculative Realism,” Artforum, Summer 2015.

[3] Cox, Christoph, Jaskey, Jenny and Malik, Suhail. 2015. “Introduction,” Realism Materialism Art. Sternberg Press: Berlin. 27.

[4] “Feminism, notably, has traditionally allied itself with materialism insofar as it has attended to the concrete material circumstances of women’s bodies, lives… and conditions of labour. Yet feminists have also tended to be suspicious of claims to scientific and metaphysical truth, out of concern that such supposedly neutral claims are in actuality informed by an unexamined masculinist bias.” In Cox, Jaskey and Malik, 23.

[5] “New Materialism,” https:// newmaterialistscartographies.wikispaces.com/ New+Materialism. Accessed January 6, 2016.

[6] Morton, Timothy. “Charisma and Causality,” Art Review Online, 2015. http://artreview.com/features/november_2015_feature_timothy_morton_ charisma_causality/. Accessed January 6, 2016.

[7] Ibid.